Systems that treat tanker ballast water before release are a critical step in preventing damage from invasive species

In recent years, companies that transport oil through Prince William Sound have been installing systems to treat the seawater their ships take on as ballast.

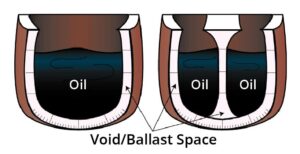

Ships pick up ballast water after unloading cargo to help stabilize the vessel during travel. The problem is that larvae and other plankton in the ocean water are also taken on board, where they can easily catch a ride in tanker ballast water to a new port.

Of particular concern to our region is the European green crab, one of the most widespread invaders on the planet. Where they become established, invasive green crab can decimate local species and habitats. Their larvae are known to travel in the ballast water of tankers, and studies have shown that they can survive in climates found in Prince William Sound.

Until recently, the most common method to reduce risk of transporting invasive species was to exchange ballast water in the open ocean. Mid-trip, the water would be pumped out of the hold and refilled with water from the open ocean. The theory is that fewer invasive species live in the open ocean and those that do are less likely to survive in a shoreline environment. However, larvae of invasive species can remain in sediments in the tank bottom. In addition, tankers that traveled between Alaska and West Coast refineries weren’t required to exchange ballast water until new regulations by the Environmental Protection Agency went into effect in late 2008. Some would exchange ballast water anyway, but if weather or sea conditions were dangerous, the exchange might not happen.

In 2018, a federal law known as the Vessel Incidental Discharge Act, or VIDA, was passed into law to streamline regulations for discharges from commercial vessels such as oil tankers. Among other changes, VIDA set a national management standard for vessels to meet. The Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Coast Guard are continuing to finalize the rules and regulations for compliance with VIDA.

Meanwhile, tankers in Prince William Sound have already installed state of the art onboard systems to treat ballast water before its released.

These systems are designed to reduce the risk of introducing organisms from ballast water. Methods include filtration, chemicals, ultraviolet radiation, electrolysis, or a combination of these methods.

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center’s National Ballast Information Clearinghouse hosts an online database with information about ballast water treatment and release: nbic.si.edu/database